Background

Much like the tale of "The Emperor's New Clothes," where truth is clouded by fear and conformity, organisations encounter similar obstacles in developing their Financial Crime (FC) Risk Appetite Statements (RAS). This paper aims to explore these issues and invite the FC community to collaborate by sharing insights and best practices. By working together, we can advance our collective understanding and make fighting FC a shared success.

Developing FC RAS is a relatively new and complex field, and opinions vary widely, like remote working! It's crucial to recognize that even well-established financial risk management disciplines, like credit, market, and liquidity risk, have their limitations. While consultants strive for solutions, the complexity of FC RAS requires a collaborative approach.

Introduction

For those unfamiliar with “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” it’s a renowned folk tale by Hans Christian Andersen that underscores key moral lessons: (i) the importance of honesty and speaking the truth; (ii) the significance of courage in challenging the status quo; and (iii) the need to think critically and not conform to groupthink.

Through humour and irony, the story reveals how individuals can perpetuate a falsehood or illusion, even when it is evident to others that it is not true. You may question the connection between these moral pitfalls and FC RAS, so allow me to explain. First, let's agree on the purpose of a RAS: “A RAS is a formal declaration by an organisation, outlining the level and types of risk it is willing to accept to achieve its strategic goals.” Now, let's draw parallels between the moral pitfalls and FC RAS:

- Truth: FC RAS often reflect the effectiveness of operational controls rather than directly expressing FC risk. Therefore, executive management does not understand the level of FC risk within their organisation or what it is willing to accept in the future.

- Status Quo: There is no universally accepted standard for measuring FC risk, leaving organisations without a clear benchmark for their risk exposure.

- Groupthink: While many FC RAS communicate similar messages, the extent of FC risk appetite adopted by each organisation can differ greatly.

Challenges In Developing Financial Crime Risk Appetite Statements

There is a common misconception that creating FC RAS is straightforward. Although it appears straightforward in theory, several inherent difficulties arise:

- Qualitative Nature: Unlike financial risks, which can often be quantified, FC risks are more qualitative. This makes it harder to measure and articulate.

- Ethical Considerations: Establishing FC RAS may involve outlining the organisation’s stance on ethical and cultural considerations, which can be sensitive and subjective.

- Regulatory Environment: The regulatory landscape is stringent and varies across jurisdictions, which must be navigated when developing FC RAS.

- Complexity of Financial Crimes: Financial crimes are diverse and constantly evolving, making it difficult to define a clear and comprehensive FC RAS. Consider the challenges that organisations have faced when dealing with fraud, sanctions circumvention, export controls violations, tax evasion, not to mention the developments in money laundering (ML) methods.

- Lack of Historical Data: Unlike credit or market risks, where historical data is plentiful, FC risks may lack sufficient historical data to inform RAS and tolerance levels.

- Lack of “True North”: Again, unlike financial risk types, there is no overarching metric that provides a clear direction or guiding principle. For instance, it is unlikely that the number of high-risk customers or Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) filed alone will drive an organisation's FC risk appetite.

The upshot is that these inherent difficulties coupled with the moral pitfalls, result in FC RAS across organizations, which are:

- Fundamentally the same: A great example of groupthink. Perhaps caused by the same FC professionals moving across organisations.

- Do not articulate risk appetite: Many equate to “insurance statements”, e.g., “We will comply with laws and regulations.” Okay, but shouldn’t this be a given?

- Refer to zero tolerance: Organisations, especially Financial Institutions (FIs), will always be exposed to criminal activities and subsequent ML. If a FI truly has “zero tolerance” to FC, then they would have to exit all their customers!

- Incorporate subtle loopholes: The term “zero tolerance” is caveated by words such as “knowingly, wilfully, consciously, intentionally, deliberately, reasonably." How these subjective terms are measured in the real world is a mystery! For instance, if you file a SAR on a client, or in fact three SARs, then does this meet the criteria?

- Refer to the control environment: A useful ploy is to simply refer to the control environment, e.g., we will not conduct business with customers with overdue periodic reviews. However, organisations often tie themselves up in knots as invariably, these situations either exist or will do so in the future. In addition, the risk tolerance is then set to a level according to operational norms. Arguably, it does not make sense setting a tolerance which you immediately breach, but doesn’t this defeat the objective?

- Acknowledge that the elimination of FC risk is not possible: Often this is combined with several of the above themes to make a statement which, on the face of it, is coherent, acceptable to internal and external stakeholders but meaningless from a risk appetite perspective, e.g., a commitment to regulatory compliance and preventing FC.

At present, FC risk appetite cannot be expressed on a single axis. It is shaped by multiple, interdependent factors — industry, geography, channel, product, among others. This means appetite is not a simple 'low-medium-high' scale but a multidimensional framework. An FI may, for example, accept higher geographical risk in low-risk industries, or PEPs only in specific jurisdictions and product sets. The challenge lies in balancing and communicating these overlapping dimensions in a way that remains usable for decision-makers. FC risk appetite is not a dial that can be turned up or down. It’s a Rubik’s Cube: each move affects the others, and risk appetite must be balanced across the dimensions.

Key Risk Indicators

Many organisations attempt to address this complexity by utilising an extensive array of Key Risk Indicators (KRIs) and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). There is often confusion in relation to how these two types of measures are used. KPIs should be measures of performance, whereas KRIs should serve as warning signals for potential threats or vulnerabilities. This sounds straightforward, but in practice it isn’t, and the misinterpretation is exacerbated due to FC RAS regulatory compliance.

To illustrate this point, one commonly used KRI is the percentage of high-risk customers. However, what does "high-risk" signify in this context? Does it imply a greater likelihood of FC? The simple answer is no.

Through analysis conducted across various organisations, it has been demonstrated that there is little to no correlation between customers classified as high-risk and actual instances of FC, whether suspicions of, or confirmed. To verify this, consider all potential indicators of FC within your organisation, such as SARs, court orders, and compare them to customer risk ratings. Often, low-risk customers represent a larger portion both in absolute numbers and as a percentage of the overall customer population which demonstrate FC characteristics. Therefore, using this as a KRI does not effectively measure FC risk. While this view may be contentious, given the valid regulatory reasons some organisations have for adopting this approach, it remains ineffective for accurately determining FC risk appetite. Some may argue that additional controls for high-risk customers deter criminal activity, but I remain skeptical.

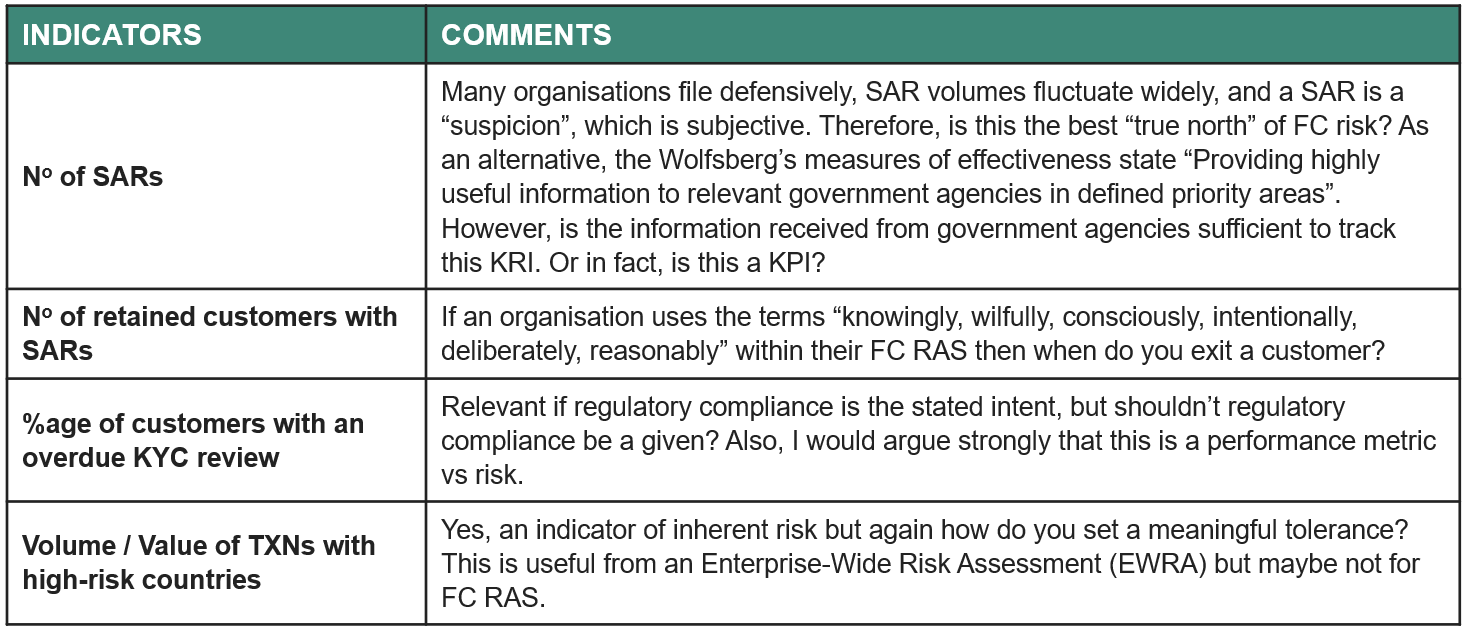

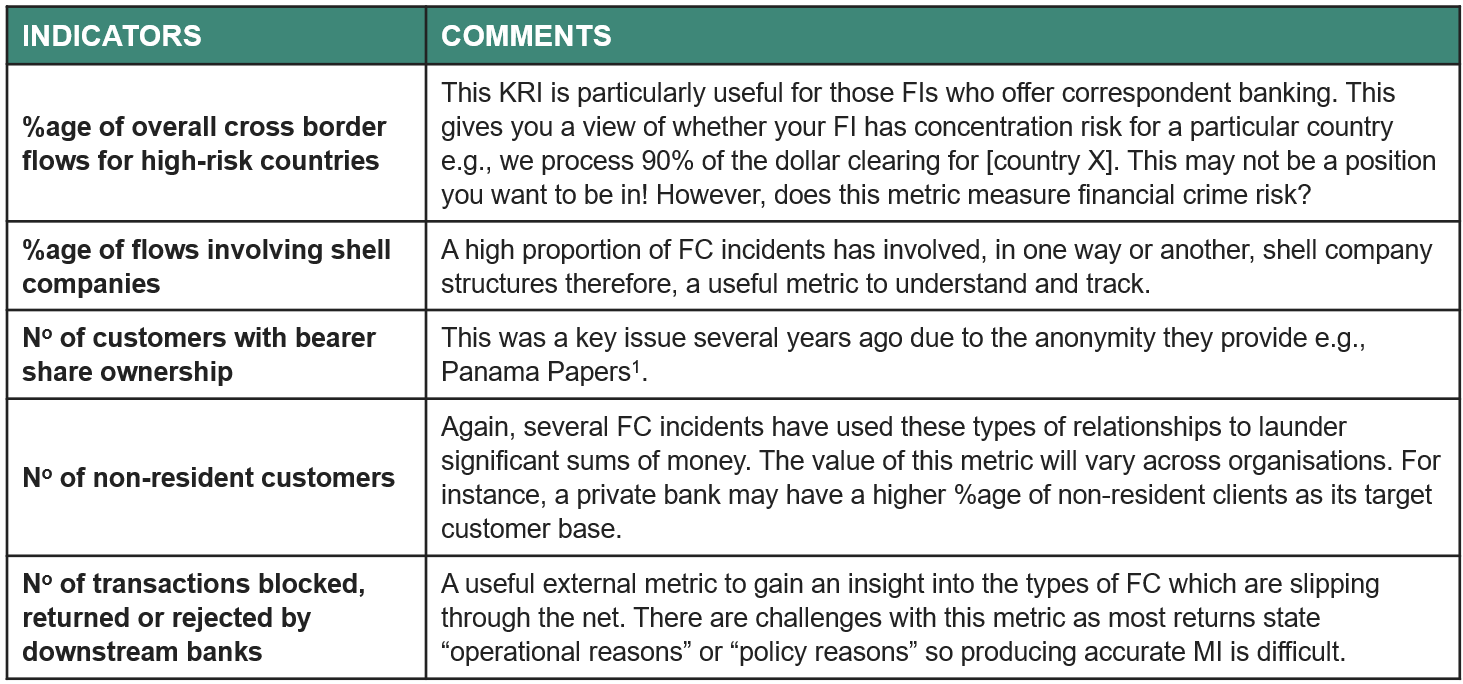

Below is a table of other metrics which are commonly used as KRIs or KPIs:

To balance the books, below are a few examples of KRIs I have found particularly useful*. Please be aware from the comments that, even for my preferred options, there are challenges in determining whether they qualify as KRIs or KPIs:

*All the above indicators resulted from one or multiple FC incidents which I have been involved in mitigating.

In essence, my point is we do not have an overarching metric or recognised methodology for measuring FC risk at an organisational level. For credit risk, we have S&P, Moody’s (other credit agencies are available!) and we have tangible metrics like loan default rates, or credit quality, but we are yet to have the equivalent for FC. The criterion of probability, the likelihood or chance that a particular event will occur, is rarely, if ever, used in FC KRIs. Maybe it never will be due to the qualitative nature of FC risk, but I think it is worth challenging and exploring further.

Perhaps, it is up to a consultancy or maybe even a regulator to come up with a holistic and robust FC risk rating which can be continually used by boards to steer their respective organisations. At present, I have not seen any board effectively use their FC RAS to steer business strategy. There are many instances where FC RAS have assisted the resolution of control failures but rarely to make tangible business decisions to reduce FC risk.

Please refer to the Appendix for a list of commonly used KRIs and KPIs used to measure FC RAS.

Potential Solutions

At the uppermost possible level, it might be acceptable to have a generic FC RAS which outlines an organisation’s intent and position on FC. In a few sentences it is impossible to articulate the breadth and complexity of the organisation’s customers, products and geographical footprint and the associated FC risk appetite. Therefore, it is critical that the overarching RAS is supported by RAS which underpin the intent:

- Level 1: Overarching FC risk statement.

- Level 2: Risk type statements for Anti-Money Laundering (AML), Sanctions, Fraud etc.

- Level 3: Individual risk statements for each risk type covering elements such as:

- Underlying risk types e.g., terrorist financing, proliferation finance, tax evasion.

- Customer risk e.g., designated persons, industry sectors.

- Product risk e.g., correspondent banking, trade finance.

It should be noted that for all the above it is straightforward to outline “prohibitions”, e.g., North Korea, SDNs, but more difficult to outline an appetite for the grey areas. For instance, what is your organisation’s stance on:

- Adult Entertainment: Legally it is permissible to process transactions, but what about the concerns about exploitation, consent, and legality?

- Investing in Controversial Industries: FIs often face dilemmas when investing in or processing transactions for industries like firearms, gambling, or cannabis, which can have negative social impacts.

- Handling Transactions for Political or Corrupt Regimes: Processing transactions for governments or entities accused of human rights abuses or corruption can implicate FIs in unethical practices.

Expanding on the comparison to financial risk types like credit, the solution might involve using a benchmark that FC RAS can utilize. The most straightforward benchmark would be the results from the EWRA. Ideally, the EWRA could help reduce risks in specific jurisdictions or business lines where the FC risk appetite has been surpassed. Typically, de-risking is implemented by lowering inherent risk or introducing new controls in response to regulatory actions or specific events. However, it is rarely done proactively based on FC KRIs.

Conclusion

There may not be a definitive answer, but I believe that an organisation claiming it has no appetite for legal violations might be missing the point. Many entities, particularly FIs, have a moral obligation to enhance their detection of FC, more accurately assess their exposure to FC risk through RAS, and uphold ethical standards. The latter presents a complex challenge, as FIs often argue they are neither global enforcers nor moral arbiters. However, I find it difficult to reconcile this view given their unique position in our society and the level of information available to do the right thing. This argument also applies to other industries such as social media and telecommunications companies.

Many boards today concentrate on control measures and regulatory compliance, often neglecting the underlying risks and predicate offenses. It is incumbent upon us to shift the focus. To effectively tackle these challenges, we must pursue transparency and innovation in FC RAS, advancing from mere compliance to a more strategic perspective.

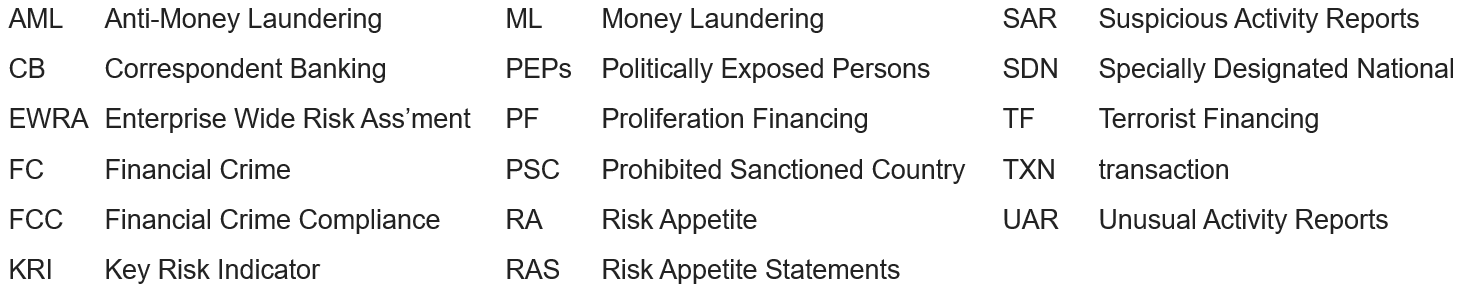

Glossary

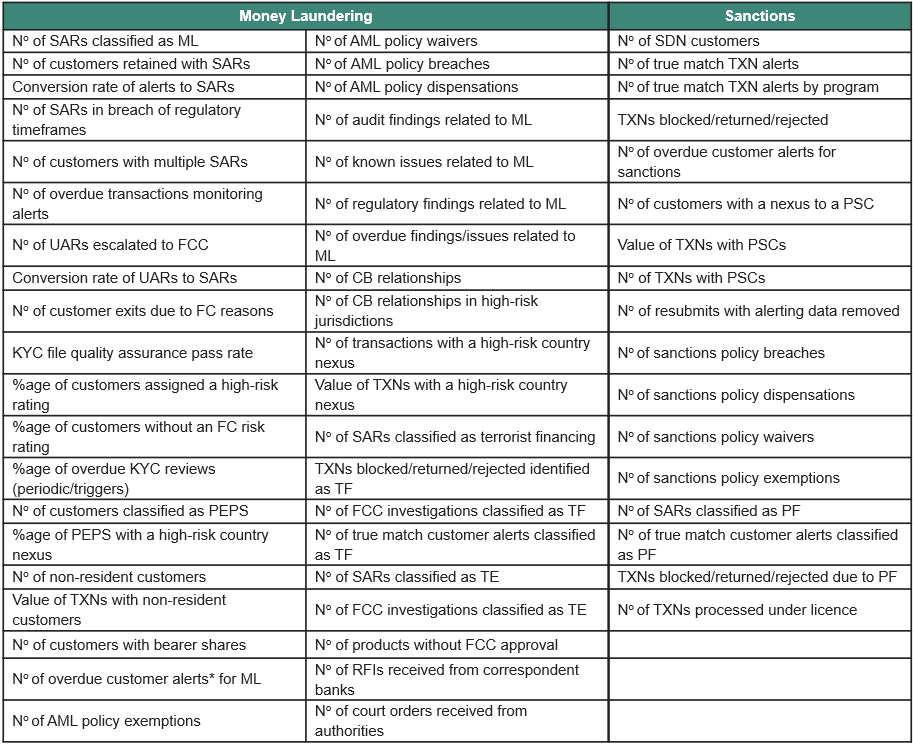

Appendix

Examples of possible FC metrics used for FC RAS:

*Customer alerts are inclusive of PEPs, adverse media, internal lists and other regulatory lists.

1Panama Papers: How assets are hidden and taxes dodged - BBC News

Sign up to receive all the latest insights from Ankura. Subscribe now

© Copyright 2025. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of Ankura Consulting Group, LLC., its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals. Ankura is not a law firm and cannot provide legal advice.